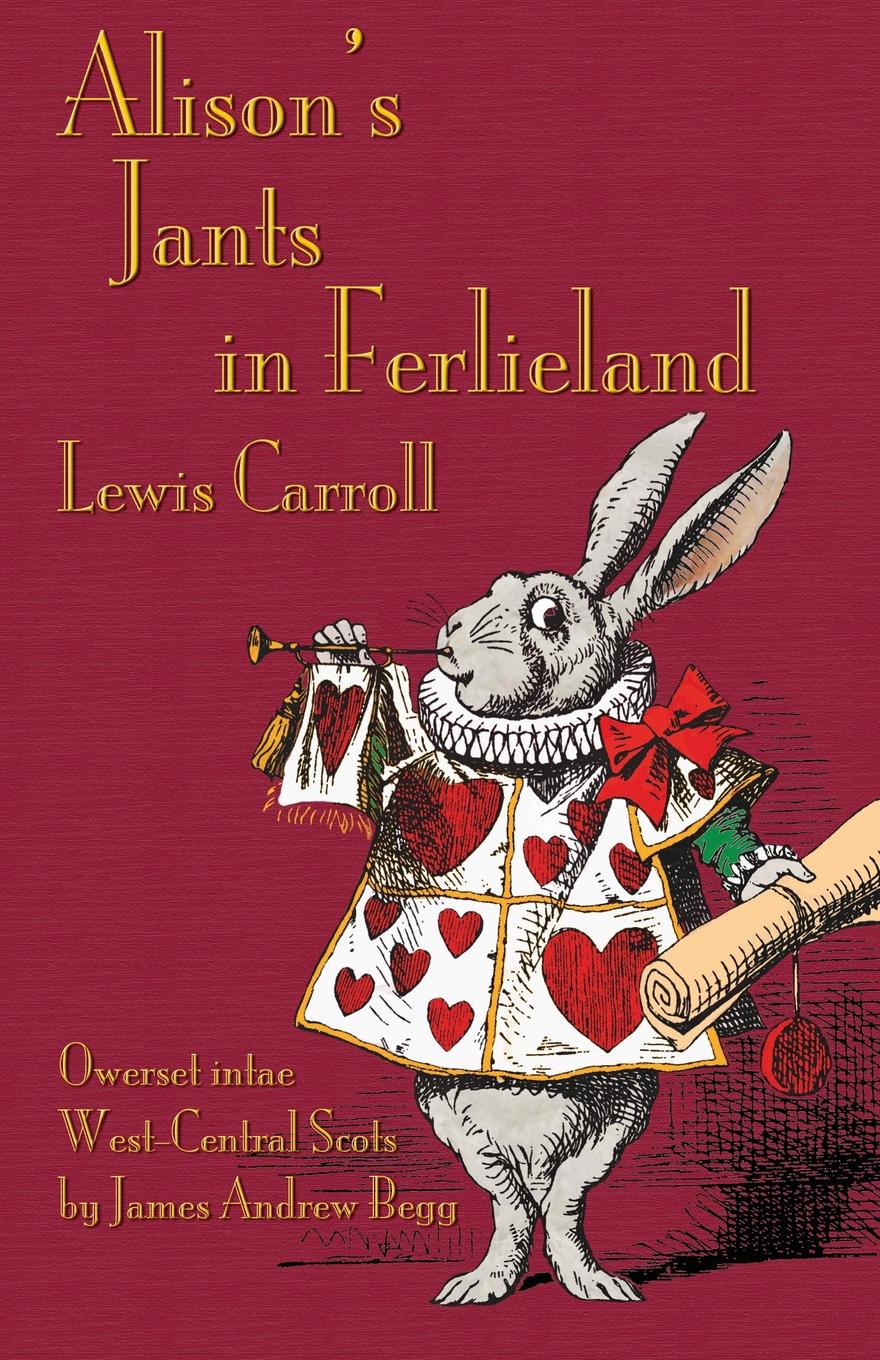

Alison’s Jants in Ferlieland

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland in West-Central Scots

By Lewis Carroll, translated into West-Central Scots by James Andrew Begg

First edition, 2013. Illustrations by John Tenniel. Cathair na Mart: Evertype. ISBN 978-1-78201-084-5 (paperback), price: €12.95, £10.95, $15.95.Click on the book cover on the right to order this book from Amazon.co.uk!

Or if you are in North America, order the book from Amazon.com!

| “Ower that airt,” the Cat said, wi a wave o its richt paw, “bides a Hatter: an ower that airt,” wavin its ither paw, “bides a Mairch Maukin. Ye can pey aither o thaim a veesit gin ye like: they’re baith daft gomerils.” | “In that direction,” the Cat said, waving its right paw around, “lives a Hatter: and in that direction,” waving the other paw, “lives a March Hare. Visit either you like: they’re both mad.” | |

| “But I dinnae want tae gang wi gyte folk,” Alison reponed. | “But I don’t want to go among mad people,” Alice remarked. | |

| “Hard lines, hen, ye cannae help it here,” said the Cat: “We’re aa gyte here. I’m gyte, ye’re gyte.” | “Oh, you ca’n’t help that,” said the Cat: “we’re all mad here. I’m mad. You’re mad.” | |

| “Hou dae ye ken I’m gyte?” said Alison. | “How do you know I’m mad?” said Alice. | |

| “Ye hae tae be gyte,” said the Cat, “or ye wadnae hae come here.” | “You must be,” said the Cat, “or you wouldn't have come here.” | |

|

||

| When Charles Lutwidge Dodgson set out one afternoon in July 1862 to invent a story about a girl disappearing down a rabbit hole, he could never have guessed that some 150 years later so many people would still be so entranced by the product of his imagination. | ||

| Lewis Carroll is the pen-name o Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, the screiver o Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, an a lecturer in Mathematics at Christ Church, Oxford. Dodgson stertit his famous bairns’ tale on 4 July 1862, when, on a bonny simmer’s efternuin, he tuik a lang jant in a rowin boat on the Thames Watter in Oxford, alangside his freen the Reverend Robinson Duckworth, Alice Liddell (ten year-auld) the dochter o the Dean o Christ Church, an her twae sisters, Lorina (aged thirteen), an Edith (juist aicht). Frae the poem at the stert o the buik, it’s plain that thae three wee lassies threipt on at puir Mr Dodgson tae tell thaim a tale. Tho sweirt at the stert, he wycely gied in, an by the en o their day oot, he had gethert thegither the makins o an awfy guid splore aboot a steirin wee lass caad Alice. Spreid richt throu the feenishd wark, furst-published in 1865, are a wheen hauf-hidden references tae the five folk on that boat on that happy day. | ||

| Thenks tae his Poems Written Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect screived by Robert Burns—born in Ayrshire twae-hunner an fifty-five years syne—the Scots Language still hauds on tae its virr an vigour in the southwest o Scotland in the twinty-furst Century; an is weel able tae add its unique flavour an zest tae the splores an jants o Alice—or in this case—wee Alison. | ||

| Settin the tale in Scotland, I felt that “Alice” soundit a wee bit “ower English” for the Scots narrative; an being weel-acquaint wi “Alison” as a weel-loued, tradeitional Lowlan Scots lass’s name, still uised frae weel afore the time o Burns till nouadays, I pickt it. On checkin its provenance in the The Oxford Names Companion (naiturally!), I fand oot tae my delicht that it cam frae a medieval Norman diminutive for Alice. A guid choice. | ||

| The Scots Language (Lowland Scots, Lallans, Doric) gangs richt awa back tae the seiventh-century Old English Tunge o the Angles frae northern Germany whae cam ower an settlt in Northumbria an southeast Scotland efter the faa o the Roman Empire. Frae there, they spreid west, ower tae the Solway Firth an up the River Nith tae Kyle in Ayrshire—the hertland o whit is nou caad the West Central dialect o Lowland Scots; an whaur this Old English tung tuik ower frae the Welsh Celtic language spoken by the native British tribes o Strathclyde in Roman times. | ||

| Ower time, baith afore an efter the Norman Conquest, their tung melled wi the words an language o Viking settlers an Fleemish merchants, wi a wee taste o French forby, tae chynge frae Old English tae Older Scots. In Scotland, whaur French influence wis less felt, this strang Scandinavian influence can still be seen an heard in baith the vocabulary and pronunciation o Modern Scots. Tho maist marked in the tung o Shetland an Orkney, it bides strang yet, even in the southwest—whaur Norse words like cleg (horse-fly), ged (pike), douk (dive), quey (young heifer), stot (young bullock), hous (house), ut (out), sang (song), brek (break)—and hunners mair (hundreds more)—are commonly uised a thousan (thousand) year on, despite a wheen centuries o threipin on at barns (bairns) tae “speak proper English and stop using that slang!” | ||

| At the same time, doun in England, this same Old English Tunge gaed a different gate, mellin wi Norman French an Latin tae gie thaim the Tudor English o William Shakespeare. Sadly for the Scots Tung, the Union o the Crouns in 1603 heralded the ascendancy o written English ower spoken Scots—an fower hunner year o the abune linguistic “ethnic cleansing”. For mony thousans o Scottish folk, even nou, still think that Scots “is just a coarse dialect”—an still tell their bairns an gran-weans tae “speak proper English and stop using that slang!” | ||

| Derrick McClure, in his scholarly Saltire Society pamphlet Why Scots Matters, pynts oot clearly—“that a form of Scots can at least be conceived, which is less closely related to English than Norwegian is to Danish”. Pit at its maist simple, The Concise Scots Dictionary—that rins tae 820 pages an juist gies the Scots-English defineitions—cuid hardly be caad a “dialect” dictionary! | ||

| The inspirin poetry o Robert Burns, ridin on the back o earlier aichteenth-century vernacular warks by Robert Fergusson an Allan Ramsay, gied a muckle heize tae the legitimacy o Poetry in the Guid Scots Tung, that still endures. | ||

| But no for serious narrative prose. For while Sir Walter Scott freely uised guid Scots dialogue braidly an brilliantly in his Waverley Novels tae gie life an virr tae his Scots worthies, his narrative prose wis aye in English, an creatit a dialogue-narrative style o screivin for Scottish novelists, that haes endured till the present day. | ||

| Sadly, the dominance o English prose in literature—an want o guid prose screivers in Scots ower fower lang centuries, haes led tae a state o linguistic illiteracy amang Scotland’s 1.54 million Scots speikers (2011 Census). | ||

| While the feck o folk micht still speik an unnerstaun Scots weel eneuch, maist wad hae bother screivin, or even readin in Scots, on account o the want o guid Scots-language prose in buikshops an libraries, an the lack o ony standard Scots spellin. Maist o the Scots words they wad uise day in, day oot, they hae never seen spelt. An this problem is made muckle waur by braid dialect differences atween the Shaetlandic o the Northern Isles, the Doric o the northeast, the rural Lallans o the south an west, an the urban Scots o Glesca—aa leadin to a rale mixter-maxter o byordinar, bumbazin, phonetic spellins o common words. | ||

| Schule teachers are nou being tellt by the Scottish Department o Education—but wi nae siller tae back it up—tae allou their pupils tae uise their Scots tung in cless as a wey o giein the bairns mair self-confidence in expressin themsels. But gin a wheen generations o teachers hae themsels been hauden-doun—aither in their ain bairnhood, or throu professional trainin—tae regaird Scots as common, vulgar, or slang; the birr for takin on this challenge haes been laith an hauf-hertit. For mony o the folk wha dinnae speik Scots tend to suffer frae that infamous, three-centuries-auld Enlightenment “Scottish Cringe”—an naiturally micht feel sweirt (or mebbe black-affrontit) at the thocht of ettlin tae speik Scots forenent a class o pupils wha, as like as no, micht speik the tung better nor thaim. | ||

| What we need nou is a generation o “enlightened” schule teachers—an mithers an faithers—wha can see the true worth o a tung that locks-in thirteen-hunner year o turbulent Scottish history—wi its rich borrowins frae a mixter-maxter o Angles, Jutes, Saxons, Danes, Norsemen, French, Flemish —an Gaels. A tung that, in aa its diversity an links, hauds on tae mair o the nation’s leevin heritage an history than aa the dumb, deid auld stanes o oor nation’s vaunty castles an stately hames. | ||

| Mebbe Alice-in-Translation cuid be a key tae the herts—an lowse the tungs—o oor bairns. For here’s Alison, a gallus, gleg wee lassie wi a guid Scots tung in her heid, that’s no feart frae a crabbit auld Queen, nor a doitit Duchess, nor crabs an cats an creepie-crawlies; an can staun her ain, wi the haverins an cantrips o a daft Hatter, glaikit Mairch Maukin, an dozent Dormous—an aye gie as guid as she gets. | ||

| A rare tare! Whit bairns cuid ask for mair? | ||

|

—James Andrew Begg Auld Ayr, September 2014 |