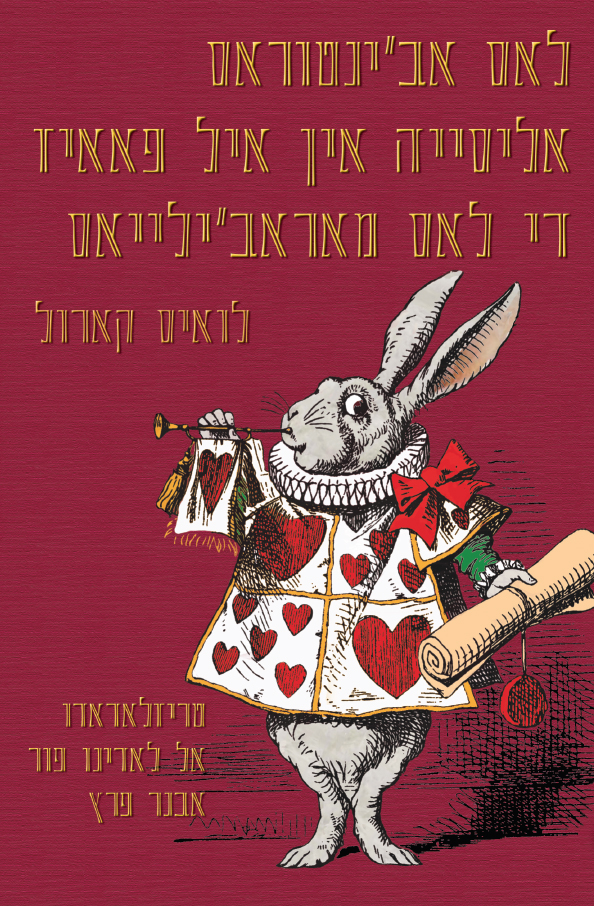

לאס אב׳ינטוראס די אליסייה אין איל פאאיז די לאס מאראב׳ילייאס

Las Aventuras de Alisia en el Paiz de las Maraviyas

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland in Ladino

By Lewis Carroll, translated into Ladino by Avner Perez

First edition, 2016. Illustrations by John Tenniel. Portlaoise: Evertype. ISBN 978-1-78201-178-1 (paperback), price: €13.95, £11.95, $15.95.Click on the book cover on the right to order this book from Amazon.co.uk!

Or if you are in North America, order the book from Amazon.com!

Also available in Latin script!

| “אין אקילייה דיריקסייון,” דישו איל גאטו, מוב׳יינדו סו פאג׳ה דיריג׳ה, “ביב׳י און בוניטירו, אי אין אקילייה דיריקסייון,” מוב׳יינדו לה אוטרה פאג׳ה, “ביב׳י און לייב׳רי די מארסו. ב׳יז׳יטה אל קין קיריס: לוס דוס איסטאן לוקוס.” | “In that direction,” the Cat said, waving its right paw around, “lives a Hatter: and in that direction,” waving the other paw, “lives a March Hare. Visit either you like: they’re both mad.” | |

| “אמה ייו נו קירו איסטאר אינטרי ג׳ינטי לוקה,” מינסייונו אליסייה. | “But I don’t want to go among mad people,” Alice remarked. | |

| “אוח! איסטו נו לו פואידיס איב׳יטאר,” דישו איל גאטו: “טודוס איסטאמוס לוקוס אקי. ייו איסטו לוקו. טו איסטאס לוקה.” | “Oh, you ca’n’t help that,” said the Cat: “we’re all mad here. I’m mad. You’re mad.” | |

| “קומו סאב׳יס קי ייו איסטו לוקה?” דישו אליסייה. | “How do you know I’m mad?” said Alice. | |

| “דיב׳יס איסטארלו,” דישו איל גאטו, “או נו אב׳ריאס ב׳ינידו אקי.” | “You must be,” said the Cat, “or you wouldn't have come here.” | |

|

||

| לואיס קארול איס און פסיב׳דונימו: טשארלס לוטואיג׳ דודג׳סון אירה איל נומברי ריאל דיל אאוטור אי איל אירה פרופ׳יסור די מאטימאטיקה אין קראייסט ג׳ירג׳, אוקספ׳ורד. דודג׳סון אימפיסו איל קואינטו איל 4 די ג׳ולייו די 1862, קואנדו ב׳ייאז׳ו אין אונה בארקה די רימוס אין איל ריאו טימז אין אוקספ׳ורד ג׳ונטו קון איל ריב׳ירינדו רובינסון דוקואורט, קון אליס לידיל (דייז אנייוס די אידאד) לה איז׳ה דיל דיקאנו די קראייסט ג׳ירג׳, אי קון סוס דוס אירמאנאס, לורינה (טריג׳י אנייוס די אידאד), אי אידית (אוג׳ו אנייוס די אידאד). קומו לו ב׳ימוס קלאראמינטי אין איל פואימה אל פרינסיפייו דיל ליב׳רו, לאס טריס ג׳וב׳ינאס פידיירון אה דודג׳סון קי ליס קונטארה און קואינטו; אי סין גאנה, אל פרינסיפייו, איסטי אימפיסו אה קונטארליס לה פרימירה ב׳ירסייון דיל קואינטו. אין איל ליב׳רו קי פ׳ינאלמינטי פ׳ואי פובליקאדו אין 5681, איגזיסטין מונג׳אס ריפ׳ירינסייאס אה איסטוס סינקו פירסונאז׳יס, קי אפאריסין מידייו-איסקונדידוס אה לו לארגו די טודו איל טיקסטו. | Lewis Carroll is a pen-name: Charles Lutwidge Dodgson was the author’s real name and he was lecturer in Mathematics in Christ Church, Oxford. Dodgson began the story on 4 July 1862, when he took a journey in a rowing boat on the river Thames in Oxford together with the Reverend Robinson Duckworth, with Alice Liddell (ten years of age) the daughter of the Dean of Christ Church, and with her two sisters, Lorina (thirteen years of age), and Edith (eight years of age). As is clear from the poem at the beginning of the book, the three girls asked Dodgson for a story and reluctantly at first he began to tell the first version of the story to them. There are many half-hidden references to the five of them throughout the text of the book itself, which was published finally in 1865. | |

| סוב׳רי טריס אספיקטוס דיפ׳ירינטיס טופי גראן אינטיריס אין אליסייה, אי איס פור איסטו קי אג׳יטי איל דיספ׳יאו די טראדואיזיר איל ליב׳רו אל לאדינו. איל פרימיר אספיקטו קונסיירני מי פ׳ורמאסייון אין מאטימאטיקה. קומו אלגונו קי איזו סו פרימיר אי סיגונדו גראדו אין מאטימאטיקה (אנטיס די דיריז׳ירסי אה לה קולטורה אי אה לה ליטיראטורה ג׳ודיאו-איספאנייולה), איסטו פ׳אסינאדו פור לה אקטיטוד דיל מאטימאטיסייאנו אי לוז׳יסייאנו קארול, קי טראטה די אינטרודוסיר און לינגואז׳י נאטוראל (איל אינגליז) אין איל קואדרו דיל לינגואז׳י לוז׳יקו פ׳ורמאל. איל ריזולטאדו איס דיב׳ירטיינטי אי פריזינטה און דיספ׳יאו פארה איל טראדוקטור קי טראטה די פריזירב׳אר איסטי אילימינטו אל טראדואיזיר איל ליב׳רו אה אוטרה לינגואה (אין מי קאב׳זו, איל לאדינו). | From three different aspects, I found great interest in Alice, and accepted the challenge to translate it into Ladino. The first aspect is my mathematical background. As one who made his first and second degree in mathematics (before turning to Ladino culture and literature) I’m fascinated by the approach of the mathematician and logician Carroll, who is trying to put a natural language (English) under the test of formal logical language. The result is amusing and presents a challenge to the translator, trying to preserve this element when translating the book into another language (in my case, Ladino). | |

| אין סיגונדו לוגאר, קומו אלגונו קי אנטירייורמינטי סי אוקופו מונג׳ו די ליטיראטורה די נינייוס (קומו איסקריטור אוריז׳ינאל אי קומו טראדוקטור), אדמירו אה קארול פור סו אקטיטוד ריב׳ולוסייונארייה אין איסטי קאמפו. קארול טרוקה איל קאראקטיר דידאקטיקו די לה ליטיראטורה די נינייוס די סו טיימפו אה טראב׳יס די לאס פארודייאס קי פוני אין לה בוקה די אליסייה. טאמביין אקי איי און דיספ׳יאו פארטיקולאר פארה איל טראדוקטור. קואנדו קארול פובליקו אליסייה, לוס קאנטיס דידאקטיקוס אוריז׳ינאליס איראן באסטאנטי קונוסידוס אינטרי לוס ליקטוריס אי איל קאראקטיר בורליסקו אירה ב׳יזיב׳לי. איסטו פ׳ואי טרוקאדו, דיסיירטו, אויי אין דיאה, קואנדו איל ליקטור סולו לו פואידי ב׳יר אה טראב׳יס די אינטירפריטאסייוניס, קומו לה די גארדניר The Annotated Alice. קריאו, דונקי, קי קומו טראדוקטור, איסטו אגורה איגזינטאדו די לה ניסיסידאד די טופאר ארטיפ׳יסייאלמינטי און פאראליליזמו אה איסטי אספיקטו די רילאסייון אינטרי לה פ׳ואינטי אי לה פארודייה. לה פארודייה אין סי איס דיב׳ירטיינטי אי באסטאנטי איפ׳יקאס. | Second, as one who previously dealt a lot with children’s literature (both as an original writer and translator), I admire Carroll for his revolutionary way in this field. Carroll reverses the didactic approach that characterized the children’s literature in his time, through the parodies he puts in the mouth of Alice. Here, too, there is a particular challenge to the translator. When Carroll published Alice, the original didactic songs were quite familiar among readers and the burlesque character was visible. This was changed, of course, today, when the reader can see it only through interpretations, like that of Gardner’s The Annotated Alice. I think, therefore, that as a translator I am now exempt from the need to artificially find a parallel to this aspect of relationship between source and parody. The parody in itself is amusing and effective enough. | |

| איל טריסיר אספיקטו איס טאמביין, אין מי אופינייון, איל מאס אימפורטאנטי אי דיפ׳יסיל: לה קאפאג׳ידאד די טראדואיזיר אוב׳ראס ליטירארייאס אי לינגואיסטיקאמינטי קומפליקסאס קומו אליסייה אין לאדינו, אונה לינגואה קי איסטה פידריינדו קאדה ב׳יז מאס סו אאודינסייה די אב׳לאנטיס. אאונקי איסטה לינגואה ג׳ודיאה אימפורטאנטי אאינדה איסטה אב׳לאדה, אין סיירטה מידידה, פור מיליס די פירסונאס, נו סי פואידי טופאר אויי אין דיאה נינייוס קי סון קריאדוס אין איסטה לינגואה. אי פור אוטרה פארטי, לה מאייוריאה די לוס אב׳לאנטיס די לה לינגואה, אנסי קומו מונג׳וס די סוס אינב׳יסטיגאדוריס, סון פרינסיפאלמינטי אינטיריסאדוס פור איל אספיקטו פופולאר די איסטי לינגואז׳י אי פור איל ריקו פ׳ולקלור קי סי קריאו אין איל, אינייוראנדו קאז׳י קומפליטאמינטי לה ריקה קריאסייון קלאסיקה אין לאדינו. קומו אינב׳יסטיגאדור דיל לאדינו, דידיקו גראן פארטי די מיס איספ׳ורסוס אין איל דיסקוב׳רימיינטו אי לה פובליקאסייון די אוב׳ראס קלאסיקאס קי פ׳ואירון איסקריטאס אין לאדינו אה לו לארגו די סוס קיניינטוס אנייוס די איגזיסטינסייה (אל פרינסיפייו אין רילאסייון קון לה ליטיראטורה איספאניקה אי מאס טאדרי קומו לינגואז׳י אינדיפינדיינטי). אדימאס, אין לוס אולטימוס אנייוס טראטי די אינקוראז׳אר אונה מואיב׳ה קריאסייון ליטירארייה אוריז׳ינאל אין לאדינו אנסי קומו טראדוקסייוניס קלאסיקאס אין איסטה לינגואה (איל פונטו קולמינאנטי די איסטוס איספ׳ורסוס פ׳ואי לה פובליקאסייון די לה אודיסיאה קון אונה דובלי טראדוקסייון, אין לאדינו אי איבריאו, פור משה העליון אי פור מי-מיזמו, 2011, 2014). מי אסירקאמיינטו אה לה טראדוקסייון אל לאדינו איס דיספ׳ירינסייאדו אי דיפ׳ירינטי דיל פוריזמו די לוס איסקריטוריס אי טראדוקטוריס די לה איפוקה די לאס לוזיס די לה סיגונדה מיטאד דיל סיגלו XIX אי פרינסיפייוס דיל סיגלו XX. איסטוס טראטארון די אילימינאר ארטיפ׳יסייאלמינטי אילימינטוס לינגואיסטיקוס נון איספאניקוס דיל לאדינו אי טרוקארלוס פור ראאיזיס אי פאלאב׳ראס טומאדאס דיל פ׳ראנסיז אי דיל קאסטילייאנו. קריאו קי איסטוס אילימינטוס נון איספאניקוס (קי פ׳ורמאן קאז׳י און קוארטו די טודו איל ב׳וקאבולארייו די לה לינגואה!) סון אונה פארטי אינטיגראל אי אינסיפאראבלי דיל לאדינו, אי סון און קומפונינטי אימפורטאנטי די סו ריקיזה קומו לינגואה אינדיפינדיינטי אוניקה, אי דיפ׳ירינטי דיל קאסטילייאנו. לוס ליקטוריס איספאניקוס די איסטה טראדוקסייון פודראן דיסטינגואיר פ׳אסילמינטי איסטאס פאלאב׳ראס אי פ׳ורמאס (אלגונאס די איסטאס מויי באזיקאס) קומפליטאמינטי דיפ׳ירינטיס די לאס קי סי אוזאן אין קאסטילייאנו. | The third aspect is also, in my view, the most important and challenging: the ability to translate literary and linguistically complex work as Alice into Ladino, a language that is increasingly losing its speaking audience. Although this important Jewish language is still spoken, to some extent, by thousands of speakers, you can’t find nowadays children who are raised in this language. And moreover, most speakers of the language, and not a few of its researchers, are primarily interested in the popular aspect of this language and the rich folklore that was created in it, ignoring almost completely the rich classical creation in Ladino. As a researcher of Ladino, I spend much of my efforts in exposing and publishing classic works written in Ladino throughout five hundred years of existence (at first in connection with Hispanic literature and later as independent language). Besides, in recent years I tried to encourage a new original literary creation in Ladino and classic translations into it (the highlight of these efforts was the publication of the first part of the Odyssey with dual Ladino and Hebrew translations by Moshe ha-Elion and by me, 2011, 2014). My approach to translation into Ladino is distinct and different from the purism of the writers and translators of the Enlightenment period of the second half of the nineteenth century and early twentieth century. They tried to artificially remove non-Hispanic linguistic ingredients from Ladino and substitute them by roots and words borrowed from French and Castilian. I believe that these non-Hispanic materials (comprising almost a quarter of the whole vocabulary of the language!) are an integral and inseparable part of Ladino, being an important component of its richness and wealth as a unique independent language, different from Castilian. The Hispanic readers of this translation can easily distinguish words and forms (some of them very basic) completely distinct from what is in use in Castilian. | |

| אין מי לאב׳ורו פארה איסטה טראדוקסיון, מי באזי אין גראן מידידה אין מי מואיב׳ו דיקסיונארייו די לאדינו די אינטירניט (“טריזורו די לה לינגואה ג׳ודיאו-איספאנייולה (לאדינו) דוראנטי טודאס לאס איפוקאס—דיקסייונארייו אמפליאו איסטוריקו”) אין איל קי איסטו לאב׳וראנדו איסטוס אולטימוס אנייוס. איסטי דיקסייונארייו, איל מאס אנג׳ו אין סו קאטיגוריאה, אין ליקסיקוגראפ׳ייה ג׳ודיאו-איספאנייולה, קונטייני אקטואלמינטי מאס די 110.000 אינטראדאס. לה אימפורטאנסייה אי לה סינגולארידאד די איסטי דיקסייונארייו איס קי קונטייני דייזינאס די מיליס די סיטאסייוניס טומאדאס די לה ליטיראטורה ג׳ודיאו-איספאנייולה, פופולאר אי קלאסיקה, די טודאס לאס איפוקאס. באזאנדומי אין איסטי דיקסייונארייו פודי ריאליזאר אונה טראדוקסייון באסטאנטי איגזאקטה דיל ליב׳רו. | In my work on this translation I have relied extensively on my new Ladino Internet Dictionary (“Treasure of Judeo-Spanish [Ladino] Language Throughout the Generations—Historical Comprehensive Dictionary”) on which I am working in recent years. This dictionary, the widest of its kind in Ladino lexicography, currently contains over 110,000 entries. The importance and uniqueness of this dictionary is that it contains tens of thousands of quotes from Ladino literature, both popular and classical, of all ages. Relying on this dictionary I was able to do a fairly accurate translation of the book. | |

|

—Avner Perez Maale Adumim 2014 |

—Avner Perez Maale Adumim 2014 |

|