Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland in Ñspel Orthography

Alis’s Advnčrz in Wunḍland

By Lewis Carroll

First edition, 2015. Illustrations by John Tenniel. Portlaoise: Evertype. ISBN 978-1-78201-051-7 (paperback), price: €12.95, £10.95, $15.95.Click on the book cover on the right to order this book from Amazon.co.uk!

Or if you are in North America, order the book from Amazon.com!

| “In ɖt drẋn,” ɖ Cat sd, wevñ its rît pw rnd, “livz a Hatr: n in ɖt drẋn,” wevñ ɖ uɖr pw, “livz a Māčhér. Vizit îɖr y lîc: ɖ’r bʈ mad.” | “In that direction,” the Cat said, waving its right paw around, “lives a Hatter: and in that direction,” waving the other paw, “lives a March Hare. Visit either you like: they’re both mad.” | |

| “Bt I d’nt wnt t g amñ mad ppl,” Alis rmāct. | “But I don’t want to go among mad people,” Alice remarked. | |

| “Ô, y c’nt help ɖt,” sd ɖ Cat: “w’r ol mad hir. I’m mad. Y’r mad.” | “Oh, you ca’n’t help that,” said the Cat: “we’re all mad here. I’m mad. You’re mad.” | |

| “Hâ d y nô I’m mad?” sd Alis. | “How do you know I’m mad?” said Alice. | |

| “Y mst b,” sd ɖ Cat, “or y wd’nt hv cm hir.” | “You must be,” said the Cat, “or you wouldn't have come here.” | |

|

||

| This book has two main aims: to present my new system of English spelling—called “Ñspel” (pronounced “Ingspell”)—and to help commemorate the 150th anniversary, in 2015, of the first publication of Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. The text is accompanied by John Tenniel’s marvellous illustrations. | ||

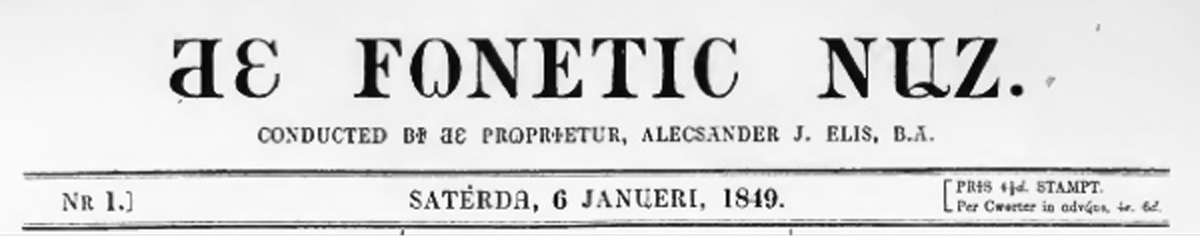

| Among his many other accomplishments, Carroll (1832–1898), aka Charles Dodgson, was a prolific inventor of word games, including a forerunner of Scrabble. A contemporary of his who was equally multi-talented and equally fascinated by the alphabet was Isaac Pitman (1813–1897) who, although most famous for his system of shorthand, was primarily interested in reforming English spelling. When Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland was first published, in 1865, Pitman’s Fonetik Institut and its journal, The Phonetic News had already been operating, in Bath, for over fifteen years. | ||

| To give a flavour of the enterprise, the masthead of the first copy of The Phonetic News is shown below, together with an extract from a progress report by Isaac Pitman in The Phonetic Journal in 1873. | ||

|

||

A lifelong friend of both men was Max Müller (1823–1900), Professor of Comparative Philology at Oxford University, where Dodgson was a lecturer in Mathematics. In one of his “Lectures on the Science of Language” at the Royal Institution (1861–1863), Müller said that:

|

||

| But while Pitman’s shorthand system was an instant success, his efforts in favour of English spelling reform had minimal practical effect, and the same could be said of all further attempts throughout “many generations” right up until today (although the controversial Initial Teaching Alphabet experiment in the 1960s deserves a mention). Thus, an article of 15th September 2010 in The Economist, entitled “Wy can’t we get it rite?”, aptly refers to the “long, distinguished and unsuccessful line of people attempting to push through English spelling reform.” | ||

That does not mean, however, that the problems of English spelling have somehow disappeared. According to James Randerson, in a New Scientist article in 2001, for example,

|

||

| In his recent book Does Spelling Matter? (Oxford University Press, 2013) Simon Horobin takes up the cudgel against reformers, arguing that our current, somewhat erratic spelling is “testimony to the richness of our linguistic heritage and a connection with our literary past.” Although this is indisputable, it suggests—in hallowed conservative fashion—that the centuries of evolution through which English spelling has passed have brought it to a state of near-perfection that rules out any further development. Given that the ancient Romans probably thought that Latin would be the world’s lingua franca for ever, perhaps continuing evolution would not come amiss in order to extend the longevity of the Empire of English. | ||

| Ñspel represents a comprehensive and radical reform, because I believe that, in the case of such a magnificently complex and subtle language as English, piecemeal and conservative proposals cause more problems than they solve. It is easy to read and write, being almost completely regular, much more phonemic than traditional spelling, and almost 30% shorter. | ||

| Nevertheless, far be it from me to wish to unleash Müller’s “violent social convulsion”! In presenting Ñspel here, I hope for no more than to highlight the question of spelling reform and to add an extra charm to the reader’s journey, alongside Alice, to Wonderland. | ||

| My thanks to Michael Everson for his unfailing support, expert advice, and meticulous editing. | ||

|

—Francis K. Johnson Coventry, August 2015 |