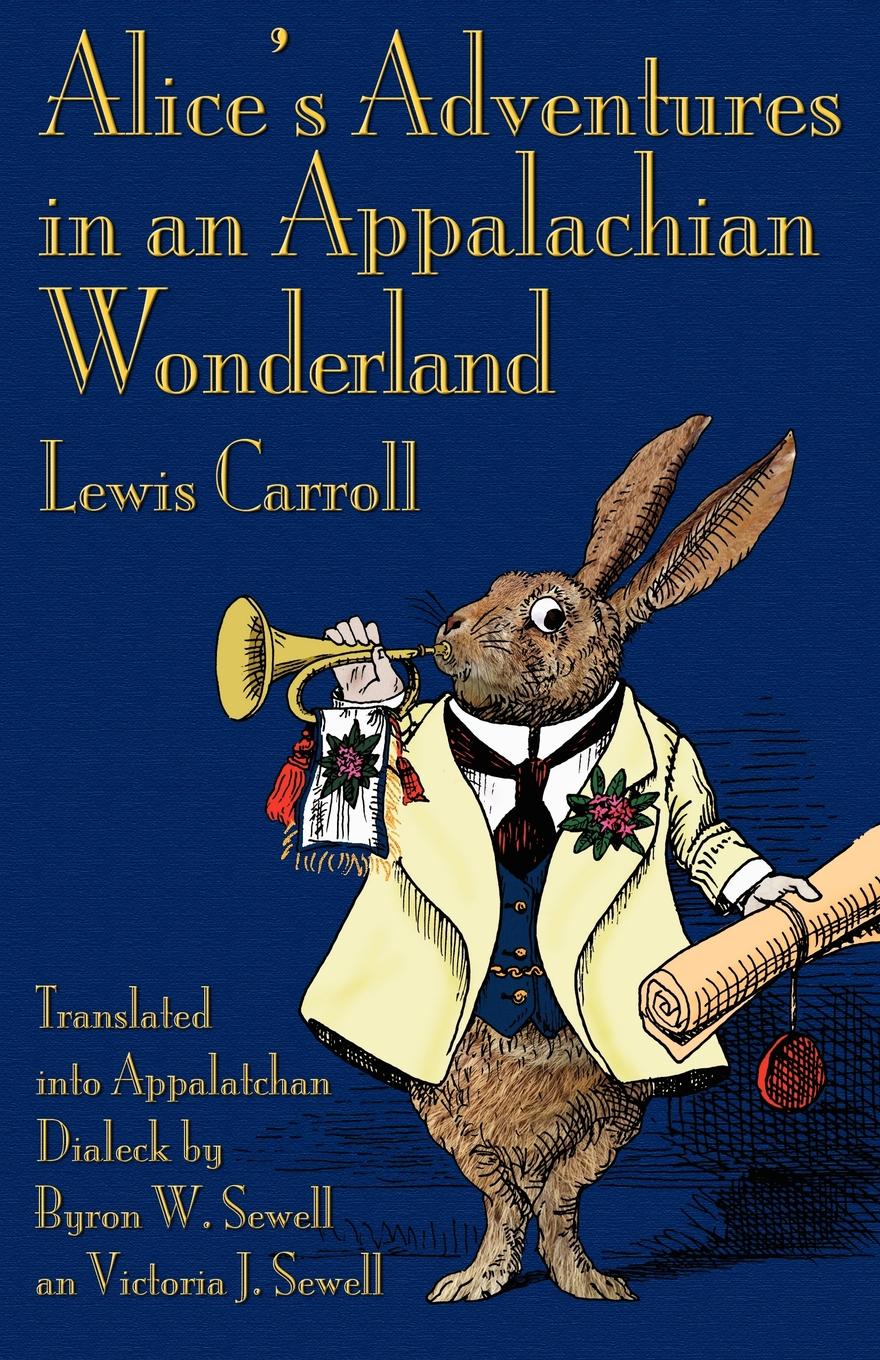

Alice’s Adventures in an Appalachian Wonderland

By Lewis Carroll, translated into Appalachian English by Byron W. Sewell and Victoria J. Sewell

First edition, 2012. Illustrations by John Tenniel. Cathair na Mart: Evertype. ISBN 978-1-78201-010-4 (paperback), price: €12.95, £10.95, $15.95.Click on the book cover on the right to order this book from Amazon.co.uk!

Or if you are in North America, order the book from Amazon.com!

| “In that direction,” the Cat said, waving its right paw around, “lives a Hatter: and in that direction,” waving the other paw, “lives a March Hare. Visit either you like: they’re both mad.” | “Up the crick,” the Bobcat says, wavin hits right paw roun, “lives an ol bar what thinks he’s Chief Cornstalk: an down the crick,” wavin t’other paw, “lives a Civil War Vetran who fitt on both sides, agin hissef. Visit whichever you like: they’s both tetched.” | |

| “But I don’t want to go among mad people,” Alice remarked. | “But I don’t wanna go mongst tetched folks,” Alice remarks. | |

| “Oh, you ca’n’t help that,” said the Cat: “we’re all mad here. I’m mad. You’re mad.” | “Oh, you cain’t hep thet,” says the Bobcat. “We’re all tetched here. I’m tetched. You’re tetched.” | |

| “How do you know I’m mad?” said Alice. | “How you know I’m tetched?” says Alice. | |

| “You must be,” said the Cat, “or you wouldn't have come here.” | “You must be,” says the Bobcat, “or you would’n’a come up here in these high hollers.” | |

|

||

| Lewis Carroll's classic Alice's Adventures in Wonderland has been translated into over a hundred languages, from French to Japanese to Esperanto. In this translation into the rich dialect of the Appalachian Mountains, the translators have treated the story as a folktale, in order to create the sense that the reader is listening as an adult tells the story to a child. The story has been transported from Victorian English to post-Civil-War West Virginia, into an Appalachian setting appropriate for the dialect. | ||

On Dialect OrthographyPublishing text in an unstandardized orthography is a challenge. A balance must be found between faithfulness to the sounds of the dialect and legibility to an audience who reads the standard language. Engish dialect spellings are nothing new, of course: from Robert Louis Stevenson’s representation of Scots in Kidnapped to Mark Twain’s representation of Missouri dialect in Adventures of Huckleberry Finn various approaches have been taken. Often these approaches make use of what is known as “the apologetic apostrophe” to mark letters from the standard language which have been “dropped”.Such spellings tend to create a distracting visual clutter; this was recognized in the 1947 Scots Style Sheet and the 1985 Recommendations for Writers in Scots, both of which discourage the apologetic apostrophe while retaining it for ordinary purposes. Many of these recommendations apply easily to the linguistic features of Appalachian English, and have been followed in the text used in this book. Since the reader may appreciate a summary of the orthographic conventions used here for the Appalachian dialect, a list is given below.

Michael Everson |

||